The Wild East

by Jopie Sanchez

As part of celebrating Leonor Will Never Die, MilkTea commissioned Jopie Sanchez to offer our audiences an introduction into the world that inspired Martika Ramirez Escobar’s vision.

When one thinks of exploitation films, The Philippines isn’t the first words to roll off the tongue. How could a country in Southeast Asia be the hotbed for something that originated in the United States? Yet, when one delves deep into the creation of these films, The Philippines plays a vital role in most of them. Martika Ramirez Escobar’s endearing feature debut Leonor will Never Die puts into spotlight this era in Filipino cinema that has otherwise faded into obscurity.

Popularised in the 60s and 70s, exploitation films came about when a film censorship code was created to preserve the image of Hollywood. With the lack of big-ticket actors, they sensationalised controversy through the themes they would tackle to attract audiences and were distributed outside of the mainstream channels. These films would feature sex, nudity, drugs, violence, and gore. Low in budget, they explored filming in other locations that would be more favourable to these limitations which is how they ended up in what they would call the Wild East or The Philippines.

The Philippines, having amicable ties with the US during this time of post-Vietnam war, was the ideal candidate.

Labour was cheap, safety standards were lax, resources were available, and “exotic” locations were plenty. The country was obscure enough to be able to paint it into what it needed to be for any story. The locals looked like a mix of different nationalities that it was easy to portray films featuring other cultures. For a paltry sum, you could get stunt men to do whatever was asked of them with total disregard for safety precautions. There were jungles and cityscapes to play around with and transform. Furthermore, prior to foreign producers setting up camp, there was already a thriving movie industry, and the fascist government at that time was supportive of the opportunity because it meant an inflow of cash and mileage for the acclaim to be used as propaganda.

It all began in the 60s when Kane W. Lynn, an American G.I. retired in The Philippines, contacted Eddie Romero, a popular director at that time who eventually became a National Artist for Cinema in 2003. He brought up the idea of producing these movies locally. Along with Gerardo de Leon, they started Hemisphere Pictures which was the first company to make American co-productions in the country. These movies were then distributed abroad where they were well-received. For their Blood Island film series they brought in John Ashley as lead actor. He ended up staying as a producer afterwards and he invited Roger Corman, founder of New World Pictures which is considered the expert on genre films, to come to The Philippines. Corman visited in the 1970s and started shooting films in the country then.

With the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, local movie screenings were subject to censorship. However, this did not apply to those screened abroad mostly because the movies did not indicate The Philippines as a location and foreign producers were able to pay to keep shooting. They would even be able to hire the military for helicopters, supplies, and to stage battle scenes, which led to the production of more films in the Wild East. The most popular one being Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in 1979. Coppola himself was one of Corman’s proteges.

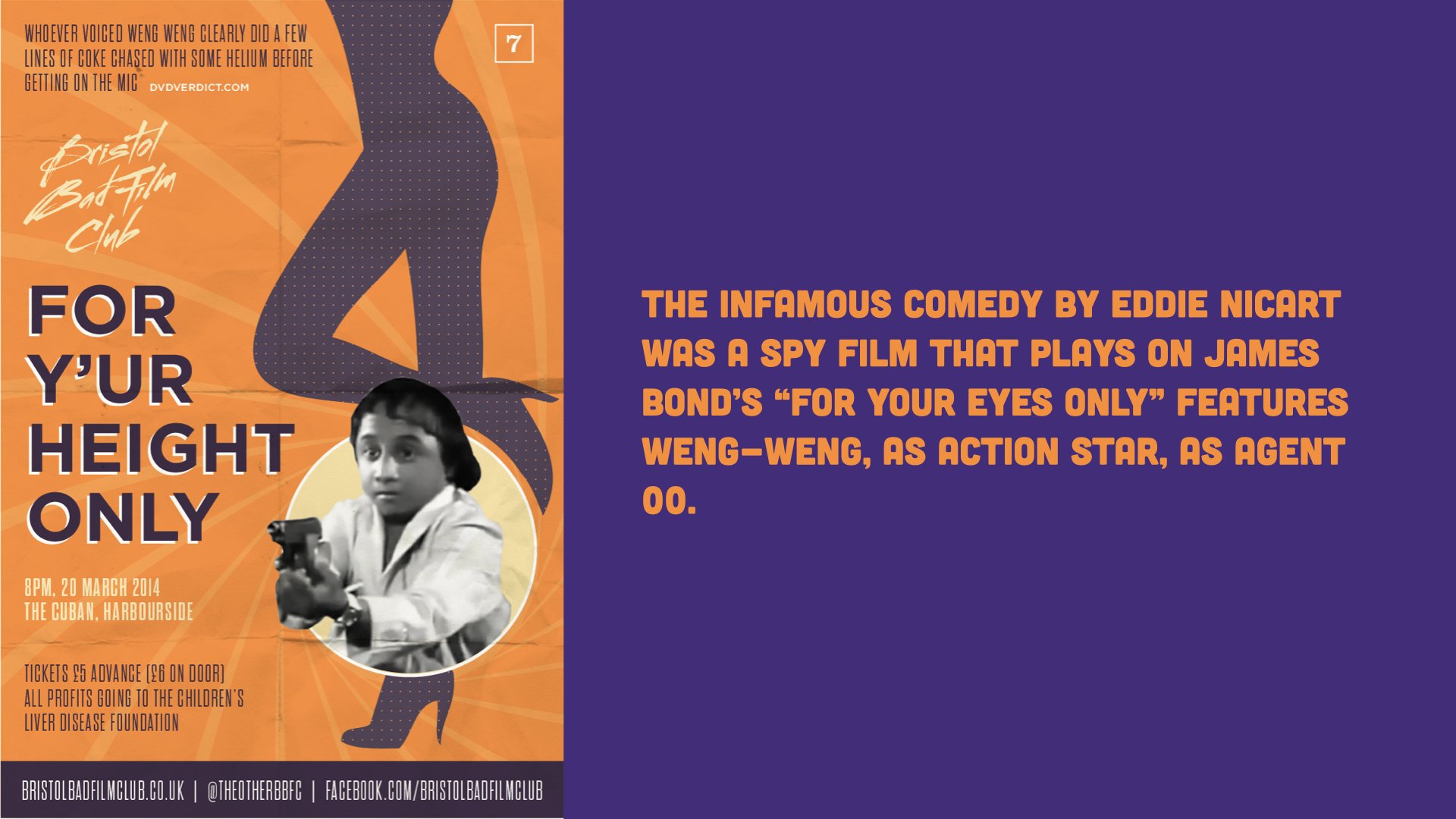

This lack of protocol when it came to foreign productions was liberating for local directors shooting for a foreign market. Other directors followed suit and went into the exploitation film genre, like Cirio Santiago, Bobby A. Suarez, and Eddie Nicart, who directed the popular For Y’ur Height Only in 1981 featuring action star, Weng-Weng.

In the late 70s, however, the landscape of global cinema was changing and known directors took inspiration from exploitation movies to use the method to make A-budget films. Critics would compare these movies with the B-movies and changed the way audience would watch films. Eventually, Grind Houses and Drive-ins started to close and the exploitation films went straight to video, having no venue available to screen their material. It also became harder to shoot in The Philippines with the political climate as the Marcos regime went full-throttle into its fascist dictatorship.

Yet, the landscape of local cinema in The Philippines changed forever moving forward from this time period. When the foreign productions left, what remained was an entire industry already accustomed to the shooting conditions they were subject to. Leonor will Never Die lives in the aftermath of this. To date, you can still see the influence of exploitation films in an institution that still grapples with limited budget and opportunities. Yet, we move forward in the name of storytelling, entertainment, and pursuit of catharsis.

Jopie Sanchez is a freelance photographer, writer, translator and subtitler based in Quezon City, Philippines.